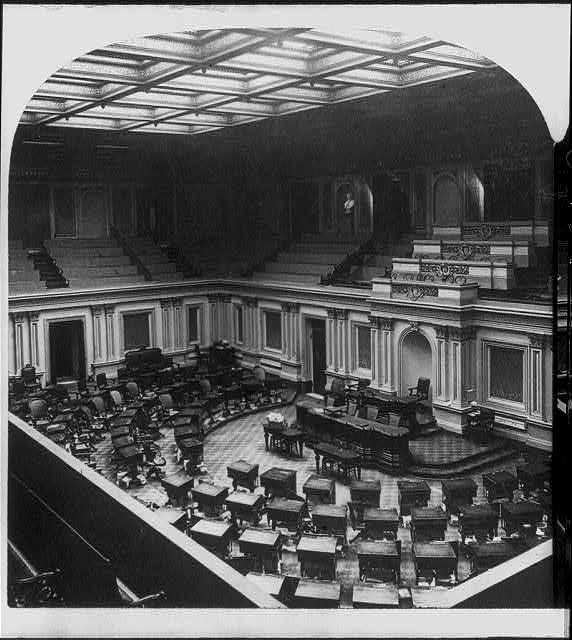

Hello? Is there anyone here? The U.S. Senate chamber, 1891. Source: R.K. Bonine via the Library of Congress.

Last month, Sen. George Helmy (D-NJ) gaveled the Senate to order. The clerk then read a communication from Senate President Pro Tempore Patty Murray (D-WA) declaring Helmy authorized to perform the duties of the chairman.

Thereafter, the Garden State senator announced to the handful of chamber staff who were the only other occupants of the Senate that the body stood in recess until next week. He tapped the gavel and then exited the chamber less than a minute after the whole process began.

This scene is all but certain to repeat itself through mid-November absent President Joe Biden calling Congress back to session to pass emergency hurricane relief aid. Senators — Mr. Helmy excepted because he’s on a four-month appointed Senate stint — are back in their home states running for reelection and raising money for themselves and their parties.

Meanwhile, an immense logjam of legislative work remains undone. The Senate did not pass a budget resolution this spring, nor did it enact any of the dozen annual spending bills. The Senate’s most recent calendar of business lists 70 pages of bills on matters large and small awaiting votes.

Professor Steven Smith, who holds positions at both Arizona State University and Washington University in St. Louis, told the Washington Examiner in an email that the chamber has suffered a “dramatic decline in cross-party legislative negotiations.” The number of floor amendments has “reached modern lows,” and the “number of committee hearings and markups has plummeted.”

More than a few senators from each party have for years grumbled about the state of the “world’s greatest deliberative body” for years. “This place sucks,” retiring Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) once groused. But it is not just a few squeaky wheels, says James Wallner, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute and a former Senate staffer. “No one seems to be particularly happy. Everybody seems to be frustrated” because senators have been reduced to roles akin to factory workers on an assembly line.

Next month, senators will have an opportunity to make changes when the parties return to Washington. With Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) stepping away from the post after what will be a record 18 years helming Senate Republicans, including six in the majority and 12 in the minority, GOP senators will pick their next leader. Whether that person is majority leader or minority leader depends on the outcomes of the Nov. 5 elections. On the Democratic side, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) is expected to stay atop his party’s hierarchy, no matter the election results.

Whether Republican senators will hard-bargain and insist on reforms in exchange for their votes is anyone’s guess.

One factor in the backlog is the Senate’s work schedule, which is truncated. The average American was back at work right after New Year’s Day. Senators this year did not show up at the Capitol until Jan. 8. While in Washington, the Senate usually conducted official business on a Tuesday-through-Thursday schedule. Of the 41 weeks that had passed at the time of writing, senators have been absent from Washington for “state work periods” for 15 of them.

However, absenteeism is not the only factor accounting for the chamber’s lack of legislative productivity. The Senate spends an inordinate amount of its floor time voting on nominations to the executive and judicial branches. Eighty-one of the 100 Senate votes taken since May 1 were for nominations. In every instance, senators had to vote twice: first to invoke cloture, and prevent a filibuster, and second to approve the nomination.

University of Georgia professor Anthony J. Madonna suggests the chamber might “push to reduce the number of Senate-confirmed executive nominations” to make space for legislating.

He observed, in an email to the Washington Examiner, that “the rise in the percentage of votes in the Senate on nominations isn’t sustainable and both parties seemed pretty annoyed by the politicization of certain military nominations.” But doing that would mean deferring more frequently to the White House, which may not fly among the most partisan senators.

Should the Democrats defy expectations and win a majority in the chamber, they might move to curb the filibuster or abolish it outright. Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris, who, as vice president through Jan. 20, 2025, can sit and vote in the Senate to break ties, is on board with that idea, as is Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR). He and his former Senate staffer, Mike Zamore, published Filibustered: How to Fix the Broken Senate and Save America earlier this year. They think the legislative logjam can be broken by eliminating filibusters on motions to bring legislation to the floor and reinstituting a talking filibuster.

The moment is especially ripe for Republicans to push for changes. Polls show the party likely to win the chamber, and its long-term leader McConnell is stepping aside. Three legislators have thrown their hats into the leadership race: Sen. John Thune (R-SD), the No. 2 Senate Republican; Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), who previously held that GOP leadership post; and Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL), who is likely to win reelection this year for a second, six-year Senate term.

Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) recently issued a letter to his GOP colleagues encouraging them to choose a leader who will revive the chamber as a lawmaking body. “We have the chance to strengthen the Senate, empower individual members, and ensure that the voices of the American people are heard once more.” Lee advocates several reforms, including reserving floor time to vote on appropriations bills and allowing amendments to bills unless three-quarters of Republicans agree to disallow them.

One former longtime Senate leadership staffer who asked the Washington Examiner to remain anonymous warned that “attempting to change the culture of the Senate by changing the rules of one caucus will weaken all Republicans, not just the leader. That’s clearly what happened on the House side.” One reason majority leaders have curbed amendments and debates is because they became weaponized. Senators used their own time on the floor to do things to embarrass members of the other party or even troll their party in front of the C-SPAN cameras. What’s wrong with the Senate, in part, is the erosion of the norm of collegiality and trust.

Wallner is skeptical that rule changes are needed to return the Senate to health. He argues that senators should quit fearing tough votes and open debate and stop deferring to their leaders. “All you’ve got to do is wake up in the morning, put your feet on the ground, and start legislating.”

Kevin R. Kosar (@kevinrkosar) is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and edits UnderstandingCongress.org. This column previously apperd in the Washington Examiner magazine.

Stay in the know about our news and events.