As it scrambled to pass a continuing resolution and avoid a government shutdown at the end of 2024, the 118th Congress ended much as it began—with serious doubts as to whether America’s legislature can rise to the level of bare competence. The House of Representatives is mainly adrift because of the difficulties Republicans had in electing a Speaker in January 2023 and the consequences of that struggle for the House Rules Committee. Understanding the House’s current malaise requires understanding the degraded state of its deliberations, which in turn requires digging into the nitty-gritty of how it considers bills.

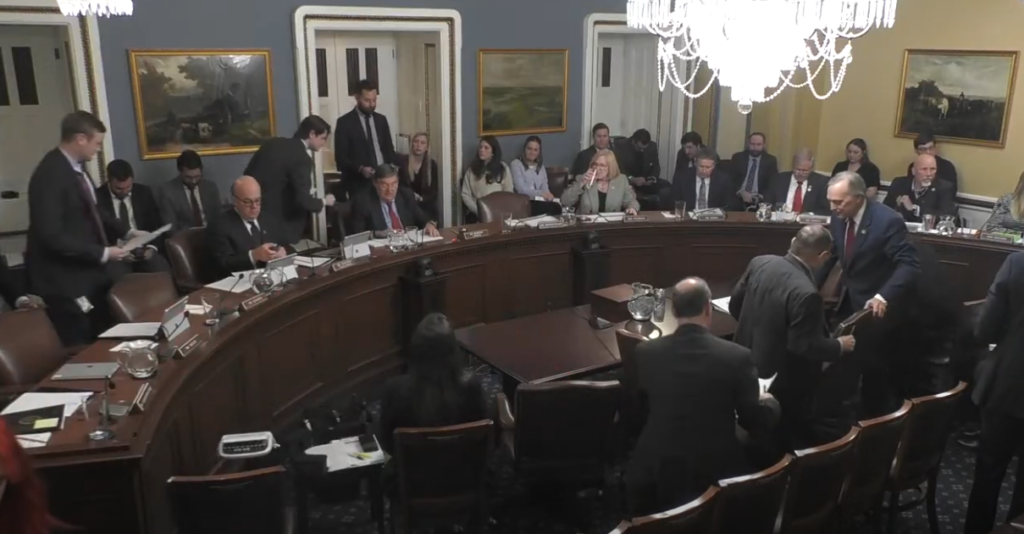

The Rules Committee is a peculiar institution that is little noticed by ordinary Americans but is central to the operation of the House. As its name suggests, it has jurisdiction over the chamber’s own rules of procedure, but those are generally settled in the first days of a new Congress. Strangely, the House mostly ignores those rules when structuring its proceedings.

Instead, legislation today is almost always considered in one of two ways. First, there is “suspension of the rules,” a procedure by which a two-thirds majority hurries a bill along to passage without much debate. Second, bills can be brought up under special orders (called “rules”) tailor-made by the Rules Committee and adopted by the whole House.

Until this Congress, textbooks of procedure could straightforwardly explain that small and uncontroversial bills would be moved through suspension, while big and controversial bills would move under procedures agreed to by the Rules Committee. These rules are endlessly adaptable. They can allow for lots of debate and consideration of amendments (usually when the House organizes itself as the Committee of the Whole), or they can shut off debate entirely and force members to vote. In teeing up a bill for consideration, they have traditionally also debated many of the substantive issues implicated, offering a “dress rehearsal” for the floor debate itself in a way that ought to improve deliberation.

The Rules Committee is the only one in the House set up with a vast imbalance favoring the majority, which gets nine members to the minority’s four. In recent years, the committee’s chairman and majority have worked hand in glove with the Speaker of the House. It is largely through the Rules Committee that the majority party exercises its effective control of the House agenda. For many years, it has been standard practice to take straight party-line votes on every rule, with all members of the majority voting “yea” and all members of the minority voting “nay”; until this Congress, the last time a rule vote failed was in November 2002.

With that background in place, we can now turn to the 118th Congress, which began on January 3, 2023.

Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) was the presumptive choice for Speaker after Republicans retook control of the House in the 2022 midterms, but he had some implacable enemies within his conference. Though he easily won the support of a majority of Republicans in their party vote, 19 Republicans initially refused to support his nomination on the House floor. It took 15 rounds of voting over four days before he was able to get over the hump with the help of former and future president Donald Trump. What gained him the support of the largest group of holdouts was his promise to include three dissident Republicans on the House Rules Committee: Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX, the informal leader of process-focused skeptics of McCarthy), Rep. Ralph Norman (R-SC), and Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY), who supported McCarthy but is famously cantankerous and skeptical of leadership).

That transformed the Rules Committee. Rather than nine allies of the Speaker, it would now be split into three blocs: six leadership-friendly Republicans, four Democrats, and three Republican skeptics. Both Roy and Massie have been outspoken critics of the leader-centrism of the House in recent years, and especially the tendency to force members into take-it-or-leave-it deals to fund the government, which are often rolled out just ahead of Christmas precisely because lawmakers’ desire to return home for the holidays is the most effective goad available. Although it was not easy to imagine the skeptics teaming up with the Democrats, it was clear from January 2023 that putting through the Speaker’s favored rules would no longer be a sure thing.

McCarthy’s speakership enjoyed a very brief honeymoon. At the end of January 2023, the Rules Committee reported an open rule—one that gave all members of the House a chance to offer amendments—on an energy bill, the first in many years. But by the spring, McCarthy faced a debt ceiling impasse. The House needed to pass an increase of the statutory debt limit, which would also be acceptable to the Democrat-controlled Senate and President Joe Biden. Many people believed that there was no bill that House Republicans would accept that would fit the bill; what turned out to be true was that there was no bill McCarthy could shepherd through without enraging and permanently alienating the right wing of his conference. He negotiated what became the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 and duly went to the Rules Committee to schedule the bill for debate. They barely consented to report it out, 7-6, with Roy and Norman voting no, while Massie reluctantly assented. But beyond the committee, many Republicans decided that McCarthy did not have their interests at heart. Breaking with years of uninterrupted partisan support for the Rules Committee’s outputs, dozens of them revolted and voted “nay” on the rule. Since this was a deal that Democrats wanted to see pass, they waited for Republicans to finish voting, and 52 of them gave their votes; the rule passed 241-187 (GOP 189-29, D 52-158).

The bill’s passage (314-117) on May 31 steered the country clear of a debt default, but for McCarthy, it was a disaster he never recovered from. In early June, a dozen Republican members torpedoed a rule on the floor to demonstrate their pique and threatened to block all rules until McCarthy somehow expiated his sin. They killed two more rules in September. For all these difficulties, most observers expected that McCarthy would manage to limp along through the congressional calendar, enduring the slings and arrows that go with the job of Republican congressional leader in the post-Tea Party age. Instead, he was unceremoniously cast out after Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) decided to put his party loyalty to the test.

After he emerged from a complicated, drawn-out battle to replace McCarthy, the new Speaker, Rep. Mike Johnson (R-LA), promised he would be more inclusive: “The job of the speaker of the House is to serve the whole body, and I will. I’ve made a commitment to my colleagues here that this speaker’s office is going to be known for decentralizing the power here.” Most of Johnson’s colleagues find him more attentive than McCarthy, but in practice Johnson has done anything but decentralize. Under his leadership, the House depended on suspension to move several pieces of controversial legislation, including the continuing resolution that averted a government shutdown in late December 2024—the final version of which was introduced about an hour before the vote on final passage. Member input in the final stages of the legislative process occurs almost exclusively by bending the ears of top leaders, with amendments mostly prohibited.

Because passage under suspension requires the support of two-thirds of members, some may wonder if there’s anything wrong with relying on it to move legislation through the House. These defenders might point out that although suspension leaves little room for floor debates and cuts off all possibility of amendment, neither of those activities has been constructive in recent years. Yes, suspension minimizes formalities, but plenty of informal deliberation can still occur between legislators both in the public sphere and privately. Negotiation is alive and well behind the scenes.

The problem with this defense is that it requires we place extraordinary trust in our top partisan leaders, who decide among themselves what ought to be in the bills that will be rushed to passage. And, to put the matter gently, we are not in a high-trust moment. When matters are decided behind closed doors, many citizens suspect they are being sold out—and plenty of members are willing to voice those concerns. Given how little input most members have into the content of final deals, it is unsurprising that they object to the whole process.

Many congressional debates are, in fact, quite stale, but it hardly follows that we are better off skipping straight to the end of the process without bothering with public debates. Reason-giving in a public forum is the essence of republican self-government. Legitimacy is created as much by the “how” as by the “what,” and that is true even if hefty supermajorities support bills. When skeptics of the procedural status quo, like Massie and Roy, call out the process as imperious and complain that their valid criticisms have been ignored rather than thoughtfully rejected, the lack of a public record makes it impossible to write them off.

Withered deliberation is at the heart of many of our most intractable policy issues. The Congress’s ability to deal with immigration and border security, for example, has been poisoned by immigration hawks’ decades-long sense that their perspective was being systematically excluded from debate by bien-pensant dealmakers who derided critics as racists or xenophobes. Even when leaders have supported big deals (as in 2007 and 2018), they have not structured the process to include all voices, and the hawks have found various ways to tank their vaunted bipartisan deals.

Members ought to resist the desiccation of their branch of government—but, for now, they nearly all prioritize acting as loyal members of their partisan teams. Some of the House members who threatened to vote against Johnson in the 119th Congress expressed their dissatisfaction about the structuring of the legislative process, but they ultimately did not put up much of a fight, let alone outline a clear alternative vision. And every one of them supported a new rules package (unlikely to be changed in mid-course) without any public dissent, even though there were few changes from the rules governing the 118th. (The one small concession the dissenters got was prohibiting moving suspension bills on Thursdays and Fridays.) Process reform is, at most, an abstract aspiration rather than a program being actively sought.

And what of the Rules Committee itself in the 119th? As of this writing, it is still without a chair; the expectation is that the dissidents will keep their three seats, though Massie may be swapped out for a substitute. The need to pass a Republican president’s agenda may tamp down on dissent, but Republicans’ highest hope seems to be docility. Despite the many tensions between factions in their ultra-thin majority, there is little sense of the need for deliberation, either in the committee itself or on the floor. By neglecting the need to work through difficulties through open debate, Republicans are setting themselves up for explosive failures on the floor.

Philip Wallach is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of Why Congress (Oxford University Press.) This essay previously was published by the Civitas Institute at the University of Texas at Austin.

Stay in the know about our news and events.